100 years of walking with Ulysses

With Homer’s Odyssey at its heart – an epic tale of prolonged journeying to a place once recognised as home – James Joyce’s Ulysses feels more relevant to our displaced, post-pandemic mindset than ever before.

A novel of circles – Leopold Bloom’s grand, circulatory loop of the city; characters thinking themselves into circles; episodes that lock into each other like gears – that has been called the most difficult book to read since its publication exactly 100 years ago, can feel eerily familiar to anyone who has lived a portion of the past two years in a 2km radius.

Because of this, now might be the ideal time for readers – many of whom have spent those two years exploring the city through pandemic walks – to meet the novel anew.

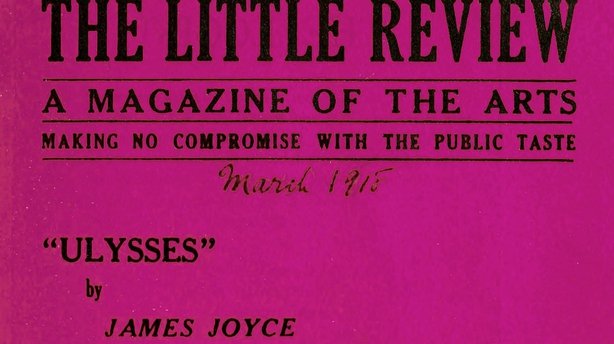

Ulysses was originally serialised in The Little Review, ‘a magazine of the arts’

Joyce’s Dublin was in many ways, of course, markedly different from our own today. A colonial city striving towards independence, on the cusp of a devastating Civil War; a poverty-stricken metropolis teeming with tenement slums.

Crucially, the city as presented to awed readers in 1922 was fundamentally a memory, a literary time capsule of another era – 1904 – painstakingly constructed by Joyce. Even this long look back over his shoulder feels familiar to anyone who has flicked through old photos, messages, Tweets and Instagram posts pre-March 2020, desperate to get back.

But its publication also cemented a version of Ireland that was claustrophobically stagnant, as then as it was in 1904. How does the world that Ulysses burst into in 1922 compare to now?

A draft of a chapter of Ulysses, in Joyce’s own handwriting

My first pandemic walk was on March 20th, 2020, I have the photo to document it. The 2km radius was freshly in place, the Liffey now less a fluid passage through the city than a fixed border. On that first walk I passed a bar attempting a revamp of its facade, possibly trusting the lockdown would be just a few weeks, with a can of red paint freshly spilled on the path.

Over the next few weeks, I watched as the paint congealed, hardened, scuffed and flaked, a milestone on my 7km loop to the boundaries of my radius and back again. Like for so many others, those walks were meditative, but also just something to do. It didn’t feel epic, but its ability to transform the mundane certainly was.

Not much happens in Ulysses, either, but walking is structurally central to the novel, Anne Fogarty, Professor of James Joyce Studies in UCD and Director of the UCD Research Centre for James Joyce Studies, says. “It’s fundamental to the idea of plot and the narrative. It puts everything in circulation. It captures a kind of purpose and a kind of aimlessness at the same time.”

A walk with Joyce, from the new RTÉ One documentary 100 Years Of Ulysses

In Ulysses, Joyce’s characters, especially protagonist Bloom, are caught in a contradiction of a city. For them, walking isn’t the leisurely activity it is today. With a tram system that comes to a halt, as in the Aeolus episode, walking was one way to overcome the blockages of the bustling city.

Dublin at the time was both stagnant and thriving, as Fogarty notes, with Joyce moving on from the idea of the “paralysed city” he presented in Dubliners. “The centre of Dublin was navigable and relatively intimate”, she says. “It was feasible to walk from one end to the other.”

However, there’s very little for his characters to actually do aside from shop, chat and drink. Bloom himself even makes the distinction between “peaceable pedestrians” and “famished loiterers”, painting the city as one divided between those who walk with purpose – be it for work or socialising – and those who languish with nothing to do.

2018: Janet Moran plays Molly Bloom in The Abbey Theatre’s adaptation of Ulysses

Caught in the middle are the central women of Ulysses. While there are many lesser female figures populating the novel, the ones we meet are either confined to the home like Molly Bloom, or walk the street as prostitutes.

“It would still have been seen as suspect for women to walk around”, Fogarty says. One hundred years later, and very little has changed in this sense.

As Fogarty points out, one of the few female characters we meet with any sense of autonomy is Gerty MacDowell, who has a limp, which “says something about her confinement, as well as just physically.”

That feeling of stagnation dominated the early lock downs for those of us in Dublin. For young people in particular, many of whose plans had been scuppered by the crisis, it was a time of restlessness, of feeling hemmed in by a claustrophobic city, cut off from progress.

We find a figure just like this in Ulysses in the form of Stephen Dedalus, who has returned from Paris where he glimpsed the aesthete’s lifestyle he so craved in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Called home to Dublin to sit at his mother’s deathbed two years prior, he struggles to reintegrate into the city, feeling disappointed with his job as a history teacher, and resentful toward those around him. Throughout the novel he drowns his sorrows in drink, until mention of him fades away toward the end.

Stephen Rea as Leopold Bloom in the 2003 film Bloom, adapted from Ulysses

For Bloom, however, walking is the distraction he indulges in. It is a way of deferring the unpleasant, of temporarily ignoring the uncomfortable realities of his life. “Think you’re escaping and run into yourself”, he says in the Nausicaa episode. “Longest way round is the shortest way home.”

His narrative is dominated by his knowledge that his wife, Molly Bloom, will consummate her affair with his rival Blazes Boylan. Rather than confront this betrayal head on, Bloom leaves his home for the day, busying himself with tasks, meeting friends and flirting with other women, all while obsessively thinking back to what is happening in his home at 7 Eccles Street.

Many of us spent the first few weeks of lock down trying to root ourselves to our homes in ways we possibly hadn’t in years. For a lot of us, “home” had become the office, the gym, the bars and cafes and restaurants we visited the most. It was anywhere but home itself.

The homeward journey is central to Homer’s Odyssey, and consequently to Ulysses. Home, as Fogarty points out, is a tricky subject in Ulysses, not least because this is colonial Dublin. These are inherently displaced characters: “Literally everyone is homeless. No one quite has a place to go to.”

It’s through walking, however, that Bloom begins to process the reality of his situation. Bloom’s path through the city is “material” on one hand, Fogarty says. “But he’s also using it to diagnose what’s happening in Dublin.”

Ultimately, Joyce’s walking characters hold the key to his vision for the city, and for us. “I think Joyce does want us all to be mobile, and he’s thinking about reawakening Dublin and getting Dublin going again”, Fogarty says. As the centenary of the archetypal walking novel coincides with the reopening of the city, Ulysses presents walking as the ultimate act of transgression, liberation and progression.